The world’s most compelling and aesthetically pleasing works of art are found in Islamic architecture and art. Islamic art is known for its elaborate geometric designs, arabesques, calligraphy, and vibrant mosaics, which have been appreciated and studied for centuries. Since the foundation of the Islamic empire in the seventh century, Islamic art and architecture have spread throughout the world, influencing the architectural and creative styles of numerous nations.

The extensive history of Islamic art and architecture, including mosques, palaces, and other buildings, will be discussed in this article. We will analyse the various forms, methods, and influences that have formed this dynamic art form as we explore the development of Islamic art and architecture from the early Islamic period to the Golden Age of Islamic civilisation. We will also examine some of the most notable works of Islamic art and architecture, such as the Taj Mahal, the Alhambra, and the Great Mosque of Cordoba.

Islamic Art

The term “Islamic art” refers to the visual arts created beginning in the seventh century by both Muslims and non-Muslims who resided in or were subject to the dominion of culturally Islamic populations. Because it has spanned over 1400 years and numerous locations and populations, it is therefore a very challenging art to define. Additionally, this art is not of a particular time, place, or media. As opposed to this, Islamic art encompasses a variety of artistic mediums, such as architecture, calligraphy, painting, glass, pottery, and textiles.

Islamic art encompasses all forms of art from the diverse and rich civilizations of Islamic societies and is not just limited to religious art. Christian religious art traditions are very different from Islamic religious art. The word assumes a religious significance in art since figural depictions are typically thought to be forbidden in Islam, as shown in the tradition of calligraphic inscriptions. Islamic art includes calligraphy and the decorating of manuscript Qur’ans, as the word has both religious and artistic value.

Mosques and opulent gardens of paradise are examples of Islamic architecture that include religious symbolism. Although there are figurative paintings in Islamic art that depict religious scenes, these paintings are mainly found in secular contexts like illuminated poetry books or the walls of palaces. Even though they have more overtly religious inscriptions, other religious art, such as glass mosque lamps, Girih tiles, woodwork, and carpets, typically reflect the same style and motifs as modern secular art.

Greek, Roman, early Christian, and Byzantine art movements as well as Sasanian art from pre-Islamic Persia all had an impact on Islamic art. Various nomadic incursions introduced Central Asian styles, and Chinese influences profoundly shaped Islamic painting, pottery, and textiles.

Islamic Art’s Themes

Islamic art contains motifs that repeat, such as the arabesque, which is a repetition of stylized, geometrical floral or vegetal designs. In Islamic art, the arabesque is frequently employed to represent the transcendent, indivisible, and infinite character of God. Some academics contend that errors in repeats

may be purposefully added by artists who think that only God can provide perfection as a sign of humility.

Islamic art has typically, though not exclusively, emphasised the representation of patterns and Arabic calligraphy rather than human or animal images since many Muslims hold the view that doing so is idolatry, which is against God and is forbade in the Qur’an. However, all periods of Islamic secular art contain representations of the human form and animals.

Islamic Architecture

The mosque is the primary illustration of the diverse styles that make up Islamic architecture. Soon after Prophet Muhammad’s reign, a distinctively recognisable Islamic architectural style that integrated Roman building customs as well as regional modifications of the previous Sassanid and Byzantine patterns came into existence.

Read More: Role of Religious Political Parties of Pakistan – About Pakistan

The Dome of the Rock

The Dome of the Rock, one of the first Islamic structures in Jerusalem, is constructed literally around a rock that is revered by all three monotheistic religions. Judaism holds that this is where God supposedly created the world and Adam, the first person. Muslims consider it to be the location from which Prophet Mohammad (P.B.U.H) embarked on his Night Journey to Heaven and returned, while Christians believe it to be the location where Abraham was told to sacrifice his son, Isaac.

Abd al-Malik, the Umayyad Caliph, began construction on the building, which was completed in 691–692 CE. The building’s octagonal design is reminiscent of a nearby Byzantine church called the Church of the Seat of Mary, which has an octagonal layout. This monument to Islam may have been inspired by a nearby example when a new people took charge and announced their arrival, just as the Roman Christians utilised the example of the Roman basilicas to plan their initial churches. The interior is entirely old, at least after the dome was rebuilt in 1022–1033. The outside was renovated in tilework.

Ancient Mosques

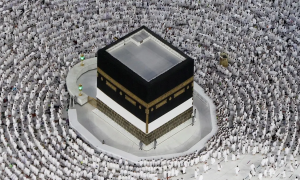

In the past, the Islamic mosque served as a place of worship and a gathering place for the neighbourhood. The earliest mosque, Prophet Muhammad’s house in Medina, is thought to have served as an inspiration for the early mosques.

One of the most important and well-preserved early grand mosques is the grand Mosque of Kairouan in Tunisia. It was built in 670 and has a minaret, a sizable courtyard encircled by porticoes, and a hypostyle prayer hall, all of which are distinctive characteristics of early mosques.

Great Mosque of Cordoba

The Umahhad dynasty in Damascus, Syria, was deposed by the Abbasids in 748–750, and they fled across the Middle East before landing on the Iberian peninsula and founding a new dynasty there. The magnificent mosque’s construction was started by Caliph Abd al-Rahman around 786.1 The Visigoths had previously built certain structures on the site, such the Puerta del Batisterio (Door of the Baptistery, which was renamed following the Christian invasion), where the horseshoe-shaped arches that came to be associated with Muslim construction were really adopted. A mihrab was also located in the qibla wall of

the Great Mosque of Cordoba. Thousands of tesserae that came from the Byzantine Empire in Constantinople, along with the craftsmen to install them, are used to embellish the large dome above it.

The tallest tower in the enclosure wall is the minaret at the Great Mosque of Cordoba. The courtyard is lined with orange trees that Caliph Abd al-Rahman is reputed to have brought there to serve as a reminder of his long-lost birthplace of Damascus.

Ottomon Mosques

In the 14th and 15th centuries, Seljuk Turk architecture was developed into the first Ottoman mosques and other buildings in the cities of Bursa and Edirne. Byzantine, Persian, and Islamic Mamluk traditions all had an impact.

Later, in the 19th century, Sultan Mehmed II would incorporate European customs into his reconstruction projects in Istanbul. Ottoman mosques, including the one Sinan built, were inspired greatly by Byzantine designs, such as those found in the Hagia Sophia.

Construction reached its pinnacle in the 16th century when Ottoman architects perfected the art of creating enormous interior spaces topped by obscenely gigantic domes that appeared to be weightless and created perfect harmony between interior and exterior areas as well as articulated light and shadow. Their mosques, like the Blue Mosque in Istanbul, Turkey, were sanctuaries of transcendently artistic and technical balance as a result of the incorporation of vaults, domes, square dome plans, slender corner minarets, and columns. At the Safavid Dynasty, architecture developed, reaching a pinnacle with Shah Abbas’s construction programme at Isfahan, which comprised numerous gardens, palaces (like Ali Qapu), a massive bazaar, and a sizable imperial mosque. The Imperial Mosque, which was built in the years after Shah Abbas I’s permanent relocation of the city, is one of the most notable examples of Safavid architecture that can be found in Isfahan, which served as the capital of both the Seljuk and Safavid dynasties.

Read More: Roots And Practice Of Sufism – About Pakistan

Muslim-Made Luxury Items

Glass Work

The most significant Islamic luxury art of the early Middle Ages was glassmaking. Islamic luxury glass was the most advanced in Eurasia for the majority of the Middle Ages, and it was sold to both Europe and China. Much of the old Sassanian and Roman glassmaking region was taken over by Islam. Aside from the fact that the region initially formed a governmental unit and that, for instance, Persian innovations were now very instantly adopted in Egypt, the transition in style was not abrupt because figurative ornamentation was not a significant feature of pre-Islamic glass.

Luxury glass was distinguished between the 8th and early 11th centuries by effects created by modifying the glass’ surface. European Hedwig glasses are an illustration of this. Beginning in the 12th century, the manufacture of luxury glass relocated from Persia and Mesopotamia to Egypt and Syria. During this time, regional factories produced less complex goods, such as Hebron glass made in Palestine.

Lusture Painting

The practise of lustre painting, which dates to the eighth century in Egypt, involves adding metallic colours while the glass is still being made. Additionally, it entails embellishment using glass threads of a different colour that are woven into the primary surface and occasionally altered by combing and other effects. Shapes and motifs taken from various media were incorporated, along with gilded, painted, and enamelled glass. A monarch or wealthy man contributed some of the best craftsmanship for mosque lighting.

Arabesque Calligraphy

All forms of Islamic art, including building and the decorative arts, frequently used calligraphic design during the Middle Ages. It is not surprising that the word and its artistic expression became a significant element in Islamic art in a faith where figural depictions are viewed as an act of idolatry. The Quran, which is regarded as the word of God, is the most revered sacred literature in Islam. Islamic arts contain numerous instances of calligraphy and calligraphic inscriptions relating to Quranic texts. However, Islamic art does not just use calligraphy on books. Calligraphy can be seen in a variety of artistic mediums, including architecture. For instance, the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, built around 691, has calligraphic inscriptions on its interior that include verses from the Quran as well as texts from other sources. Religious injunctions, such as Quranic passages, may be incorporated into secular items, especially coins, tiles, and metalwork, just as they were in Middle Ages Europe. Poetry passages, ownership or donation records, and other writings in calligraphy were also common. The Quran was not the only source for these inscriptions. Islam had a high appreciation for calligraphers, which emphasises the significance of the word and its artistic and religious meaning.

Islamic Book Painting

In Persia, Syria, Iraq, and the Ottoman Empire, manuscript painting peaked in the late mediaeval Islamic world. In the Islamic world of the late mediaeval era, Persia, Syria, Iraq, and the Ottoman Empire were the centres of book painting. The art form flourished in each region and drew inspiration from many cultural touchstones.

When the Mongols, led by Genghis Khan, stormed over the Islamic world in the 13th century, book painting first started to develop. The Yuan in China, the Ilkhanids in Iran, and the Golden Horde in northern Iran and southern Russia were among the dynasties that emerged after Genghis Khan’s death as his kingdom was divided among his sons.

Miniatures

During this time, the tradition of the Persian miniature (a little painting on paper) grew, and it had a significant impact on the Ottoman miniature in Turkey and the Mughal miniature in India. The restrictions on depicting the human form were far more flexible in illuminated manuscripts because they were a courtly art form that was not displayed to the general public. As a result, the human form is frequently depicted in this media. In 12th-century book frontispieces, influences from the Byzantine visual language (blue and gold colouring, heavenly and victorious images, symbology of drapery) were blended with Mongol facial forms. Chinese art forms, such as early adoption of the vertical format typical of books, can be seen in Islamic book painting. Peonies, clouds, dragons, and phoenixes are a few examples of Chinese themes that were adapted and used into manuscript illumination.

Persian poetry classics like the Shahnameh often received the biggest number of illustrated book commissions. The art of manuscript illumination flourished in Iran during the Safavid era (1501–1786). The Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp, a massive edition of Ferdowsi’s epic poem that includes more than 250 paintings, is the most notable example of this.

Islamic Textile

The carpet was the most significant textile created in the Islamic Middle Ages and Early Modern Periods. The creation of arts and crafts using fibres from plants, animals, or synthetic materials is referred to as the textile arts. These things could be functional or purely beautiful and opulent. Prior to the advent of Islam, the manufacturing and commerce of textiles played a significant role in Middle Eastern civilizations and cities, many of which prospered as a result of the Silk Road.

The manufacture of textiles in the area, which was undoubtedly the most significant craft at the time, came under the influence of the Islamic kingdoms as they developed and expanded in power. The carpet was the most significant textile created in the Islamic Empires of the Middle Ages and Early Modern Periods.

The Production of Carpets and the Ottoman Empire

In the Ottoman Empire, the craft of carpet weaving was extremely significant. Turkish tribes established the Ottoman kingdom in northwest Anatolia in 1299, and following the historic conquest of Constantinople in 1453, it expanded into an empire.

The large and enduring Empire, which spanned Asia, Europe, and Africa, persisted until 1922, when Turkey’s monarchy was overthrown. In the Ottoman Empire, carpets were highly prized both as ornamental accents and for their usefulness. They were employed as wall and door hangings in addition to floors, where they added insulation.

These deftly woven carpets, which were typically rich with religious and other symbolism, were made of silk or a blend of silk and cotton. Because of its beautiful weaving, Hereke silk carpets, which were produced in the coastal town of Hereke, were the most expensive of all Ottoman carpets. Usually, Hereke carpets were used to decorate royal palaces.

Persian Carpets

The Shia faith of its shahs, which was the dominant Islamic sect in Persia, set apart the Iranian Safavid Empire (1501–1786) from the Mughal and Ottoman kingdoms. Many artistic traditions have benefited from the contributions of Safavid art, particularly the textile arts.

Carpet weaving changed from a nomadic and peasant art in the fifteenth century to a well-developed enterprise that employed specialised design and manufacturing processes on premium fibres like silk. For instance, the carpets of Ardabil, which were ordered to honour the Safavid rulers, are now regarded as the finest specimens of classical Persian weaving due in large part to their use of pictorial perspective.

The export of textiles increased significantly, and Persian weaving rose to become one of the most sought-after imports into Europe. Islamic carpets were considered a luxury good in Europe, and there are numerous instances of Renaissance paintings from that era that show Islamic textiles being used in European homes at the time.

Read more: Exploring The Rich History Of Pakistan: A Fascinating Tour through Time – About Pakistan

Conclusion

In conclusion, the development of Islamic art and architecture is a fascinating tale of ingenuity, invention, and cross-cultural interaction. Islamic art and architecture have developed and adapted to new cultural and technical influences from the early Islamic period to the present, producing some of the most stunning and breathtaking creations in the entire world. The aesthetic and architectural traditions of numerous nations around the world have been influenced by Islamic art and architecture, leaving an enduring legacy. Islamic art’s distinctive geometric designs, arabesques, calligraphy, and vibrant mosaics to enthral and inspire designers and artists today.

We are continually reminded of the ongoing legacy of this extraordinary art form and the significance of cultural interaction and creativity in forming our world as we explore and admire the rich history of Islamic art and architecture.